Ran across this article. This is the problem with criminal justice reform for sake the of saving money. Its time to examine who we lock up and why. Its a conversation that will bring up a long history of racial and economic injustice. but until we do, we’ll be shifting chairs on the titanic.

Prison cuts prove fleeting. Critics say state can’t afford to lock up so many people

By Mike Ward

AMERICAN-STATESMAN STAFF

Sunday, Dec. 4, 2011

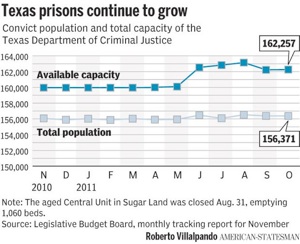

Last summer, when tough-on-crime Texas closed its first prison ever, legislative leaders were jubilant over downsizing one of the nation’s largest corrections systems by more than 1,000 beds. It was a first big step, they said, toward saving taxpayers tens of millions of dollars in coming years.

Meanwhile, prison officials were adding bunks to the other 111 state prisons, which house more than 156,000 convicts. By last week, Texas had about 2,000 more prison bunks than it did a year ago, thanks to a state law that requires the prison system to maintain some excess capacity as a cushion against crowding.

Because those beds will likely fill up — empty prison beds almost always do — Texas taxpayers could be in line for some whopping additional costs come 2013.

The situation illustrates how difficult it is to significantly reduce prison costs in a fast-growing state like Texas without confronting a tough political question: Can society afford to keep so many criminals behind bars?

“This is the adult discussion that the Legislature is going to have to have,” said Scott Medlock, an Austin attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project. “Ultimately, the problem is that we’re incarcerating too many people for too long.”

State Sen. John Whitmire, a Houston Democrat who for more than a decade has headed the committee that oversees prisons, echoes the sentiment:

“At some point, because of the costs, we have to recognize that we don’t need to waste one dollar incarcerating one person that doesn’t really need to be behind bars. We’re at that point.”

To significantly reduce the number of people in prison, state laws could be changed to reduce penalties for some crimes or to limit local judges’ discretion to mete out long prison sentences for nonviolent crimes — both of which would be unpopular politically.

About 35 percent of the convicts in prison are serving time for nonviolent crimes, according to a prison system statistical report for 2010.

The Legislature’s belt-tightening during a budget crisis earlier this year shows how difficult it is to cut prison spending, which amounts to about $4 billion for two years.

The Legislature whacked more than $60 million from prison spending in 2011.

That resulted in the closure of the aged Central Unit in Sugar Land, outside Houston. Hours at medical clinics at 34 prisons were cut, as were about 200 medical workers. Convicts are now paying $100 a year for their care, if they can, an increase from $3 a visit.

Only two meals are served on weekends, instead of three, and desserts are off the menu except for once a week. Rehabilitation and treatment programs have been downsized. More than 1,500 employees have been laid off. Prison manufacturing plants have been closed and consolidated. Parole and probation officers are supervising more offenders on the street.

To cut much more, corrections director Brad Livingston has warned repeatedly, could compromise prison security by forcing layoffs of guards and leaving convicts without enough supervision.

Still, such overall savings were virtually wiped out with the announcement last week that legislative leaders had promised to appropriate an additional $45 million to the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston to continue providing health care for two-thirds of the state’s prisoners.

Expecting that an even tighter budget may be ahead, even as prison costs — especially medical costs — increase, a variety of advocacy groups are pushing for fewer Texans in prison.

Medlock suggests that the state Board of Pardons and Paroles should release Texas’ “most medically expensive and least criminally dangerous” prisoners — a group that could include several hundred.

Ten convicts alone racked up more than $6.1 million in medical bills during 2010 — including one 45-year-old prisoner whose treatment cost more than $1.2 million, internal prison-system statistics show. Under current law, prisoners are not eligible to receive Medicaid. Parolees, however, can.

“Texas inmates aged 55 and older make up about eight percent of the state’s prison population, but account for more than 30 percent of the system’s hospital costs,” Jim Harrington, director of the Texas Civil Rights Project wrote in a letter to the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, which is reviewing the operations of the prison and parole systems with an eye toward overhaul in 2013.

“If released, much of the cost for their care would shift to the federal government, because they would be eligible for Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security Disability Insurance, etc. Likewise, parole is much less expensive than incarceration.”

But so far, the parole board has not agreed, turning down more than 90 percent of convicts who applied for a medical early release.

Burned by several headline-grabbing cases in which convicts faked an illness or disability to get out and then committed new crimes, Parole Board Chairwoman Rissie Owens has said the panel remains very cautious about approving such releases.

The Austin-based Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Center for Effective Justice is among a growing number of groups advocating for less spending on prison incarceration and more on less-costly alternative programs.

“They’re much more effective,” said director Marc Levin, who is also Texas director for Right on Crime, a national organization of conservative leaders who advocate smarter, not bigger, criminal justice budgets.

The group includes such notables as GOP presidential hopeful Newt Gingrich, tax-cutting activist Grover Norquist, former U.S. education chief and “drug czar” William Bennett and former U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese.

“There’s nothing the state can do to limit its costs (for prisons) if we keep sending more and more people to prison, if we keep expanding the capacity,” Levin said.

Among other budget-savings proposals being pushed:

• Parole to their home countries some of the 8,000 nonviolent criminals who are not U.S. citizens, a plan that was enacted into law last spring but has yet to see significant results.

• Allow counties to benefit financially for sending fewer convicts to state prison, through new state funding for local corrections programs that advocates insist would be less costly for taxpayers — and probably more effective in cutting recidivism. A bill to do this died in the Legislature last spring.

• Reform sentencing laws, and limit the amount of prison time a judge can give some nonviolent offenders. Past proposals for sentencing guidelines have died in previous legislative sessions amid opposition from elected judges and prosecutors who say it would illegally limit their authority to dispense justice based on community mores.

While more than a dozen other states have recently enacted or are seriously considering such changes, legislative leaders say they are not sure Texas is quite ready to go along.

“The challenge now is to find a way to operate a smaller system while maintaining public safety, which is the most important consideration,” said House Corrections Committee Chairman Jerry Madden. “We know how to be tough on crime. Being smarter on crime is always much more difficult to figure out.”

For Levin, the issue may be much simpler:

“At some point, we have to stop putting everybody we’re mad at in prison and reserve those cells only for the people we’re afraid of.”

http://www.statesman.com/news/texas-politics/prison-cuts-prove-fleeting-2012682.html